The Leeds town hall showcases Yorkshire’s ingenuity completely and has been used as a model for civic buildings across Britain and the British Empire, being one of the earliest and largest. It is a key part of Leeds’ heritage and serves several cultural functions. Hosting tours, concerts and performances.

The Planning

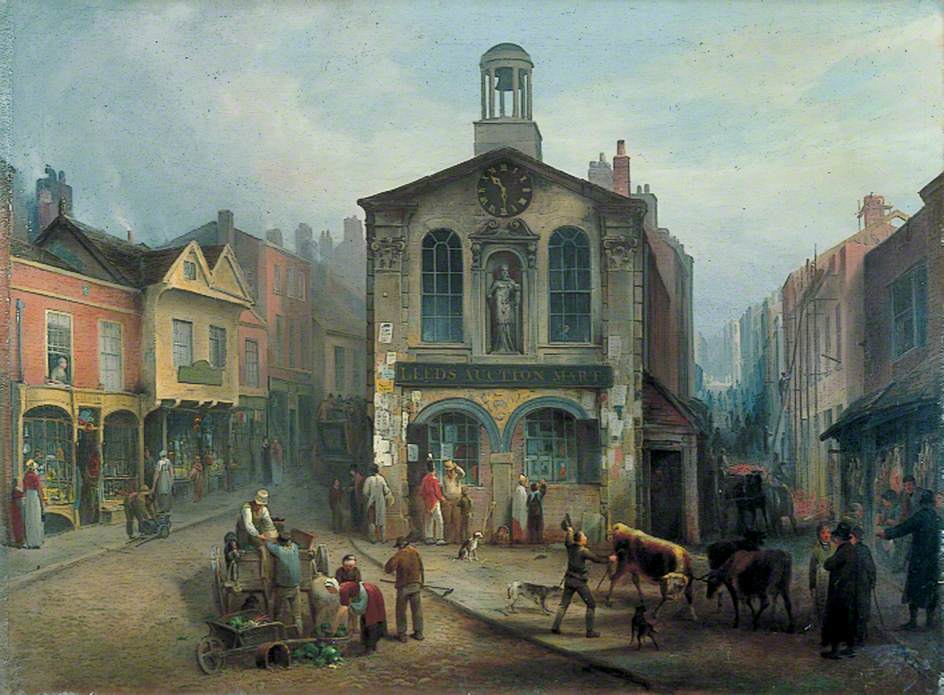

Until 1813 Leeds City Council was seated in the moot hall, which had been constructed in 1618 on Briggate. Leeds went through a large period of extreme growth in the first half of the 19th century yet was missing a status symbol. The town of Bradford took the lead in trying to elevate Yorkshire industrial towns with stately architecture with the construction of St Georges Hall. due to the competition between Leeds and Bradford, calls grew for Leeds to also have a status symbol specifically a town hall. In July 1850 Leeds town council held a public meeting to debate about the status symbol. The decision was made that a large public hall should be built. The town hall was approved in January 1851 when the motion was put to the councillors and was subsequently passed by twenty four votes to twelve. The town hall was intended to express Leeds’ emergence as an important industrial centre during the industrial revolution and symbolise the pride and confidence in the civic structure. The land was purchased for 39,500 which today is worth over a million pounds, at the time the site was on the edge of the town. The idea of a town hall did not secure universal backing immediately, as many of the Victorian politicians disliked incurring civic expenses without genuine proof of public advantage. This lead to them initially not supporting the scheme. However, they were in the minority and any motion to limit the town hall’s costs were defeated by a small majority. The support from the public was also advantageous in getting the town hall scheme moved forwards, with the Leeds Philosophical society and the Literary society being in strong support, with the Leeds improvement also seeing the town hall as an important part of Leeds’ goal of discarding its image of being an architectural backwater.

The Design

The Leeds council accepted designs from architects in 1852, using an open competition to attain submission. The brief was for a new kind of building that had not existed in England prior. The building was briefed to combine the functions of the moot halls, concert rooms and courthouses with municipal offices and a suite of reception rooms for the mayor. The ambitious brief asked for space to accommodate holding 8000 people. The brief gave no specific style constraints for the architects to use, However, neoclassical style was the unwritten assumption. Entries were anonymised and only sixteen entries were received, most likely due to the low reward and the fact that the council refused to commit to picking the winning architect. The contract was revealed to have been won by Cuthbert Brodrick a 29 year old architect from Hull who was largely unknown outside of his hometown, he later went on to design some of Leeds most noted landmarks such as the corn exchange, mechanics institute and cookridge street swimming baths. The major elements of Brodrick’s design featured a heavily Roman style, setting it aside from the others submitted which mostly took inspiration from French architecture. The town hall committee initially were hesitant of Brodrick’s competency due to his youth, this led to a renegotiation of the contract stating that Brodrick would not be paid more than the £39,000 estimate for the work costs. This was a grand undertaking for Leeds as no public building to this scale had ever been erected before.

Construction

On the 25th of July 1853 the building contract was awarded to Samuel Atack, a Leeds based builder and bricklayer. The contract was for £41,835 and included a completion target of the first of January 1856, both of these estimates were greatly underestimated. The building itself is mostly constructed of local Yorkshire stone and the foundation stone was laid on the 17th August 1853 by the mayor John Hope Shaw and a sizable crowd were present for the ceremony in which the mayor placed a time capsule into the stone’s cavity. Various problems were faced by the project including deadline pressures due to Queen Victoria’s agreement to open the building. When the army started recruitment for the Crimean war, which began in 1853, a shortage of workers and a raise in wages occurred due to the army’s manpower need. This fluctuation in workforce slowed the construction and these problems led to Atack’s bankruptcy in 1857, and several other local contractors were appointed to complete the project. Regardless of the council’s earlier doubts it now appeared determined to provide for the town hall giving finance at an unprecedented scale. The design consistently changed throughout construction such as the inclusion of an organ which became the crowning piece of the town hall and others built after followed suit including an organ. There was also a desire to include a tower in the design however the tower had some trouble passing through the council as they wanted more utility than aesthetics. A compromise was reached where the council voted to allow a roof construction which would allow the future construction of a tower, and then in march 1856 a tower was formally approved to beautify the town hall.

Opening

Despite the over running costs the town council considered the town hall a great investment. On the 6th September 1858 the Queen Victoria arrived at Leeds central railway station and was met by crowds of upwards of 600,000 people. For the festivities the streets were lined with flags, banners and streamers. The Queen stayed at the home of the mayor with tight military security. The day of the celebration also featured exhibitions of local manufacturers’ work held in the cloth hall and a full scale music festival. Local reporters started claiming that Leeds became the capital of the empire for the day as the head of the empire was visiting and in residence. The building was officially opened by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert during the ceremony, although the tower was still at this point incomplete. Vast crowds turned up to participate and watch the procession. The Queen then knighted the mayor and the hall was declared open.

Modern Day

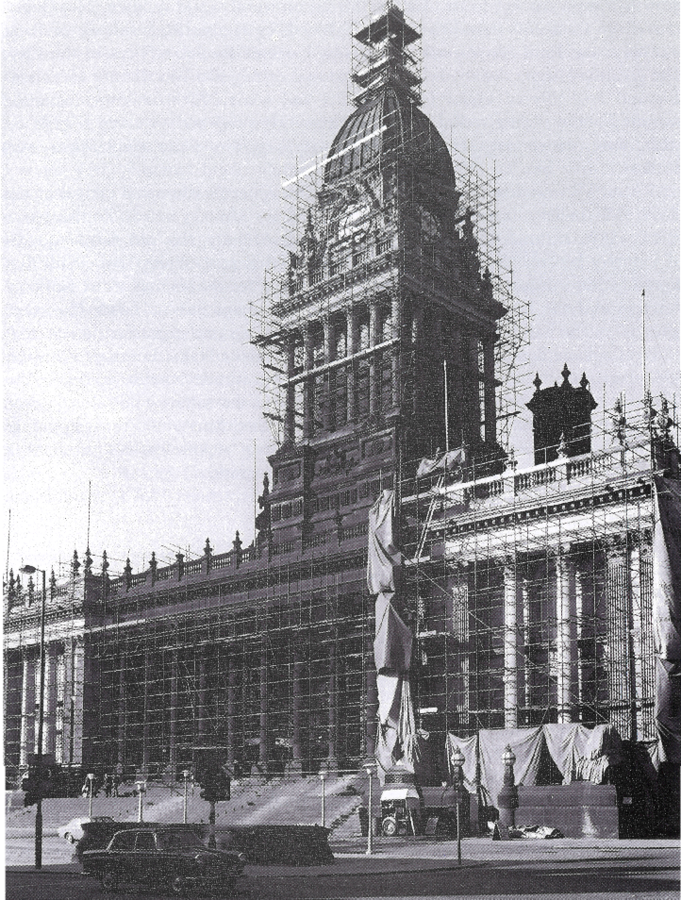

The town halls’ use throughout the modern day have changed through the times. On the 14th and 15th of March 1941 Leeds was heavily bombed by the German Luftwaffe. Most of the east side of the town hall suffered from significant damage to its roof and walls. Although the damage was repaired shortly after, evidence of this devastation can still be found in Victoria gardens. The town hall’s crypt also housed an ARP post for air raid protection and a communal kitchen to serve and help the people of Leeds; this stayed open until 1966. In 1951 the town hall achieved the recognised designated status of a grade one listed building, due to its history and heritage, protecting it against unauthorised demolition or modification. For much of the 20th century the town hall was blackened by soot and smoke from the industrial city surrounding it. Yet in spring of 1972 the building was given its first official clean up, revealing its detailed stonework. However this was opposed by the Leeds civic trust who thought it should stand as a symbol of the cities’ industrial past, and a reminder of the air pollution the city is successfully combating. A major refurbishment project of the building started in 2019 funded by the Leeds city council. The works aim to provide new seating and sound proofing, new bars and public event spaces in blocked off rooms. Along with comprehensive interior redecoration and a box office on the ground level. Works are also taking place on the clock tower and the roof replacing the tiles with welsh slate. Contractors working on the refit discovered a plaque on the dome dated from 1861, placed by the last men to work on the roof stating “ This dome was stripped and old lead put on after by Herbert Westcombe and Joseph Nett”. The building is scheduled to reopen in 2022 in time for the 2023 culture festival. The clock tower also contains a time capsule that was placed there in 2019 assembled by people working with the Leeds museums and galleries. The capsule contains; a Nando’s menu, nine Lego figurines, a mobile phone, Leeds owl artwork and a refugee education training advice service cookery book.