Have you ever wondered why railways and the City of York go hand in hand? It is largely down to the work of George Hudson, the Railway King.

Early Life

George Hudson was born in the small village of Howsham, just twelve miles north of York in 1800. He had a tragic childhood when both of his parents died before he was nine years old and was brought up by his older brothers. Upon leaving school in 1815 he became an apprentice at Bell & Nicholson’s drapery company. He worked his way up the firm and eventually received a share in the company and went into partnership with its owner to form Nicholson & Hudson, when Bell retired. The firm expanded to become one of the largest in the city and he also married his partner’s daughter, Elizabeth in 1821.

His good fortune continued in 1827 when Hudson was in receipt of a £30,000 inheritance from his great uncle. This kind of wealth bought him political power of which he used to full effect.

In the following decade he joined the Tory party and became elected to York Council in 1835. In 1838 he became the Lord Mayor of York and celebrated in customary style with an extravagant party. In the same year, Queen Victoria ascended the throne and to celebrate he organised a ‘substantial breakfast for the poor people of York and provided 14,000 of them with free grocery tickets. This man could already do no wrong and he was only just beginning.

The Railway King

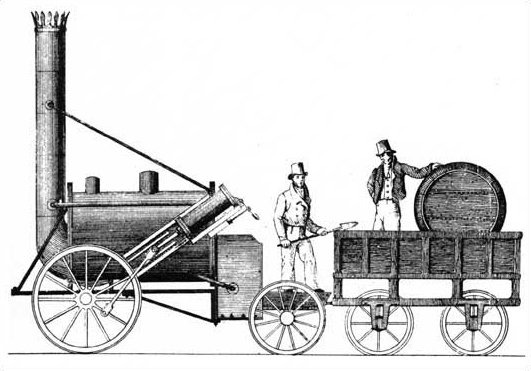

Throughout the 1830s and 40s, Britain was in the grip of ‘railway mania.’ In 1829 George Stephenson built the first steam train, known as Stephenson’s Rocket. At the trials of his new invention it could carry 20 people at an average speed of 15mph. This marked the birth of railway travel and the gradual construction of a nationwide public railway network. If you were a young wealthy man in the 1830s like George Hudson, then this was the industry to invest in.

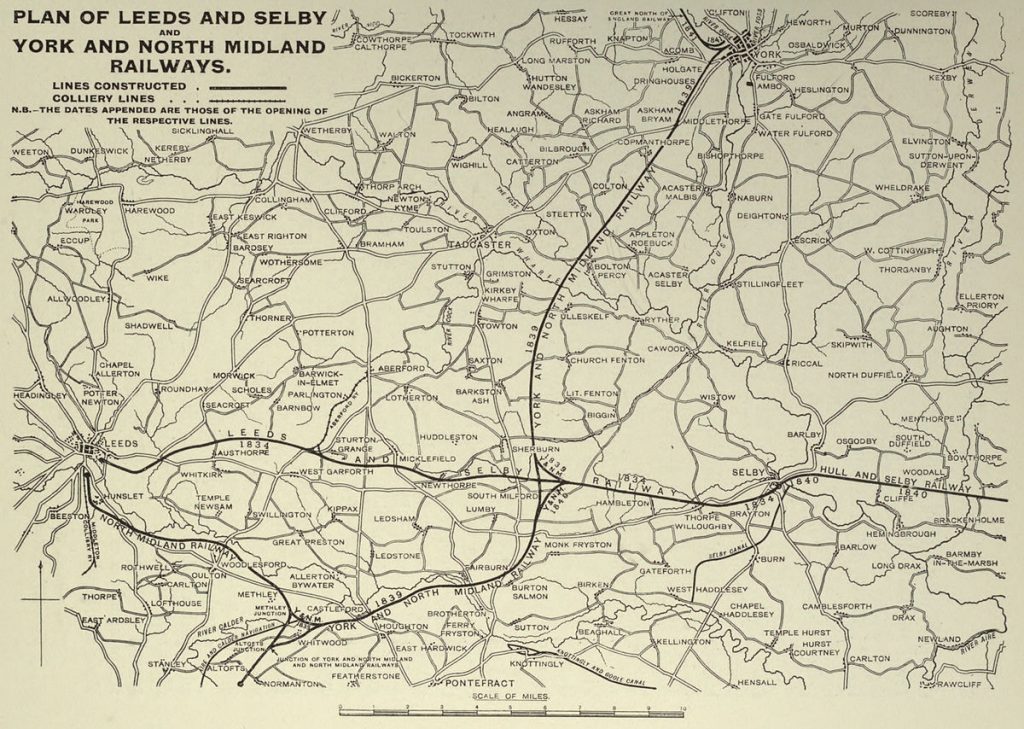

At this time Yorkshire’s railway network was primarily in West Yorkshire at Middleton near Leeds and in the northernmost tip of the county in the shape of the Stockton to Darlington railway. These were used primarily for the movement of coal and other industrial goods for the mines, rather than the movement of people. Across the Pennines the first commercial railway linking two major cities opened between Manchester and Liverpool. The success of this meant expansion to Yorkshire and the rest of the country was inevitable.

In 1834 the first railway line in Yorkshire opened, the Leeds to Selby line, which linked these two important towns and provided a faster alternative to the Aire-Calder Navigation system for transporting goods and passengers. This was developed by George Stephenson.

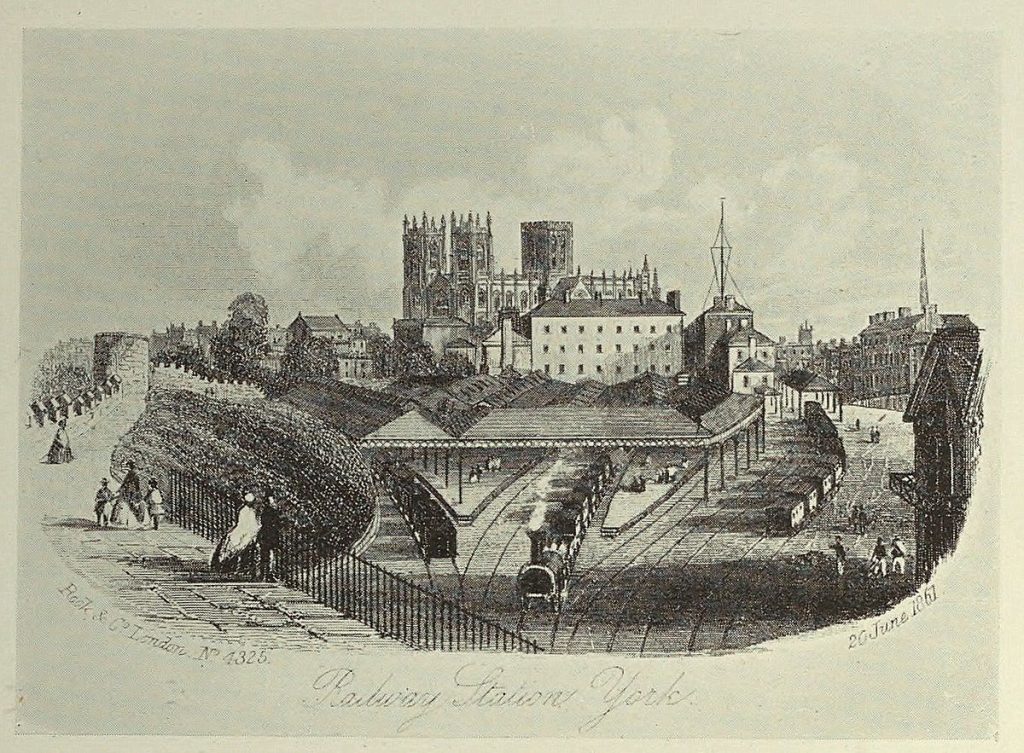

Seeing there was money to be made in this new burgeoning industry, Hudson decided to invest in a railway line project to link Selby to York. In 1837 he formed the Yorkshire and North Midland Railway Company, with himself as chairman and Stephenson as his engineer. Over the next few years they oversaw and ran the formation of most of Yorkshire’s railway network and further afield to Newcastle. This included the link from York to Leeds and the extension of the Leeds-Selby line to Hull. Importantly the rail link from Newcastle to the Midlands was originally going to be built directly via Leeds, but with Hudson’s influence it passed through York instead. This helped make his home city the epicentre of rail travel in the North of England, with rail links to the North East, West Yorkshire and The Midlands.

In 1842 he was instrumental in the formation of the ‘Railway Clearing House,’ which apportioned ticket revenue if the journey involved two different railway companies. By 1844, George Hudson controlled 1,000 miles of railway track in the North which earned him the title, “The Railway King.”

Corruption, Bankruptcy and Fall From Grace

By 1845 George Hudson was a very wealthy man. He bought Londesborough Park Estate in East Yorkshire and built his own personal railway station which linked to the Market Weighton to York line. He also owned property on the Newby Hall estate near Ripon. In 1846 he was elected as a Tory MP for Sunderland. By now his companies owned one quarter of England’s rail network. He also had 32 other projects in the pipeline at the cost of £10million. There was it seemed no stopping The Railway King!

Hudson’s world hit the buffers when in 1848 his business practices were exposed as being too good to be true. It turned out that to get the permission to build his railways he was giving out bribes to the tune of £3000 to local authorities. Furthermore he also promised the shareholders of the railway companies he owned a 6% dividend which was never paid. Thirdly, vital information regarding his share dealings was not being declared in his accounts. The investigation into his financial practices led to his resignation from all of the railway companies he ran across the North. Exposure of his crimes meant the share price of his companies fell drastically, leading to a loss of money among his shareholders. In 1849 he admitted to the charges against him and promised to pay his furious shareholders the amount they were owed. To help fund this he sold his residencies at Londesborough Park and Newby Hall, before fleeing to France.

To make matters worse, this period of time saw the rise of his arch rival, George Leeman who took over as chairman of the York, Newcastle and Berwick railway companies. In 1854 Leeman would oversee the merger of Hudson’s former businesses into The North Eastern Railway Company, with their headquarters in York.

By 1865 George Hudson had returned to Yorkshire to stand as MP for Whitby. He was arrested on his arrival and sent to York Castle prison near Clifford’s Tower. He was released after three months when friends and admirers raised the money to pay off his debts.

George Hudson saw out the remainder of his life living at a modest residence in London with his wife, Elizabeth, until his death in 1871. Fittingly The Railway King’s body was brought up to York by train and his body was buried at Scrayingham near his home village of Howsham. The former millionaire and railway pioneer died with less than £200 to his name, but his name lives on in York’s rich railway history.